July 06, 2017

The story of the Corpse can be found below if you, dear reader, ever worm your way out of the Corpse. Take heart. You can. There is life after the Corpse. There is life as long as there is a Corpse.

Exquisite Corpse: a Journal of Books & Ideas began in Baltimore as an ambitious monthly of literary production and talk. It eventually morphed into a saner quarterly schedule. It was in print from January 1st 1983 until Fall 1995, when it morphed once again into the internet journal. Exquisite Corpse: a Journal of Life & Letters. From 1995 until 2012 it uploaded world poetry, criticism, reportage, polemics and dispatches from widespread gonzo bureaus raging from Bucharest to Rio to Pusan, Korea.

Here is an essay by the editor published in "The Little Magazine in Contemporary America," edited by Ian Morris and Joanne Diaz (University of Chicago Press, 2015)

Andrei Codrescu: Exquisite Corpse[1]

From the beginning we meant to do harm. Not mean harm, the kind writers do to each other when they exact revenge for gossip intended or imagined, but the kind of harm that promotes health. American literature, poetry in particular, is sick from lack of public debate. Where I come from, Romania, it was possible for writers to fight in the morning papers and continue to do so in person at the cafe in the evening. The issues were not personal: culture was at stake. In the process, feathers were ruffled and persons became indignant. But it was clear to all that literature was bigger than us because it could not exist without passionate ferment. In the late 1960s when I came to America ferment was the order of the day. The New York poets of the Lower East Side among whom I found myself were making literature against the status quo. On street corners people handed out pamphlets against the war, calls to spiritual enlightenment, poetry written on LSD and mimeographed on speed, esoteric manifestoes and sexual proclamations. That was as complete a world of expressive assault as anyone would have wished. And yet, at the age of twenty, even all that seemed somehow insufficient.

To my natural Surrealist sympathies, the Lower East Side in the 1960s was a vast cadavre exquis, or “exquisite corpse” a form of collaboration much practiced by Andre Breton’s circle in Paris several decades earlier. To make a Corpse, one wrote or drew something and then folded the paper in such a way that the next person who wrote or drew something didn’t see what came before. The end result, when the paper was unfolded, was not the work of individuals but the creation of an esprit.

In San Francisco, where I next went, there was intense collaboration among writers, many of them refugees from New York, but the accent here was not on the printed word. Instead of street literature there were poetry readings and experimental theater.

In the mid-Seventies however, collaboration suddenly ceased. The corpse of the Sixties was suddenly unfolded and the huge wings of a terrifying bird descended on it and snatched it away. The age of the “moral majority” cultism, microchips, conservatism, Reaganism, computers, structuralism and curricula was suddenly upon us. The esprit was silenced and its practitioners went back inside, back to school, back to work, back to silence. The Outside disappeared. The metaphorical Corpse of rebellion gave way to the literal Corpse of conformism.

At the University of Baltimore where I went to teach in the 1980s they had something called a “Publications Design Department,” a graphics lab where students were always working on “magazine concepts,” I proposed that we make something people might actually want to read. I had in mind a long and skinny newspaper, patterned after Tudor Arghezi’s pre-war Romanian sheet, Bilete de Papagal, whose mixture of muckraking and high tone bohemianism had brought down two governments. I wanted to publish polemics and travelogues, capsule reviews, poetry and drawings. The name suggested itself spontaneously. It referred both to the Surrealist game and to the current state of the culture. Even longer and skinnier than Arghezi’s sheet, it was designed for reading with one hand in the subway or the bus or at the cafe. It also folded perfectly for mailing, and had the added advantage of being the occasion of instant curiosity when people first beheld its seventeen erect and six wide inches. Arghezi’s journal was literary, political, and polemical, and it earned its editor a few months’ imprisonment by the fascist government in the 1940s, and a glorious reputation for showcasing the most brilliant modern-minded writers of post WWI Romania. I didn’t share Arghezi’s fate, but neither did I expect the Corpse to be around long enough to see a great many of our contributors die before the publication did.[2] At some point, we dreamt of becoming financially solvent by selling “lifetime subscriptions,” an advertisement that didn’t specify whose lifetime your $100 would get: the subscriber’s or the magazine’s. I knew that all the contributors to Exquisite Corpse: a Monthly of Books & Ideas, would eventually be corpses, but only some of them exquisite.

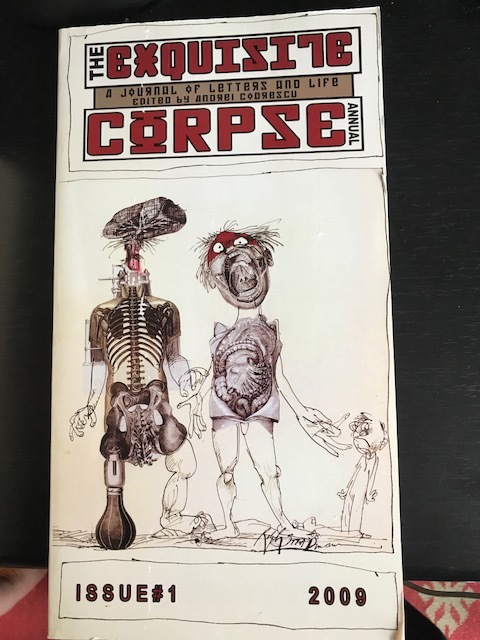

How Exquisite Corpse: a Monthly of Books & Ideas (1983-1984) became Exquisite Corpse: a Journal of Books & Ideas (a quarterly, 1984-1986), then Exquisite Corpse: a Journal of Letters and Life (1986-1996), then ExquisiteCorpse or corpse.org (1996-2012), and then the Secret Corpse (corpse.org, 2012-ongoing) is a book (or several). Moreover, this is not a book the editor could write, if only because editing and life were so closely woven that I’d have to write a fifth autobiography. The first four just skim the surface of my own life and writing: I cannot imagine what kind of oceanic epic would hold the stories of the Corpse. But if I didn’t write something, the Corpse might miss being “historical” within the very history that it helped create. There is probably little more awful than being kicked out of the history you made. Add to that the fact that, among little magazines, we have lasted at least as long as the Habsburg Empire (proportionally), and that we published most of the writers I care for, and hundreds that came to us unbidden and have (sadly) thrown their lives into the leech-infested pool of letters (or just thrown them away), and an awful kind of regret descends. It doesn’t make things easier that for the past four years I have moved to secret woods to practice “the art of forgetting” which, unlike Alzheimer’s, allows one to forget what one needs to forget, in order to make room on the hard-drive for the things one might wish to remember. Like, where did I put my glasses? Is that iPhone mine or yours?

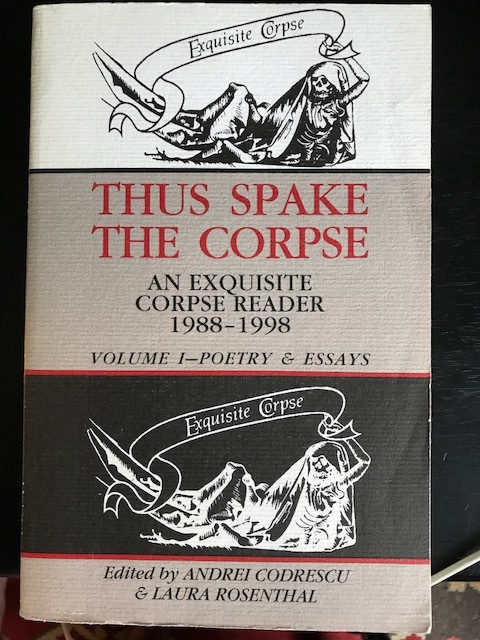

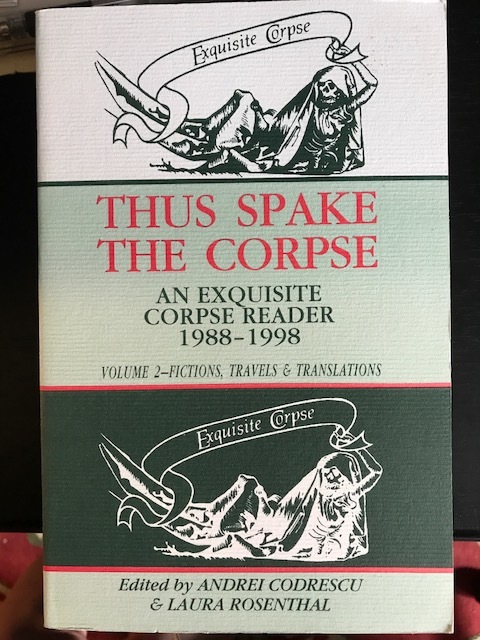

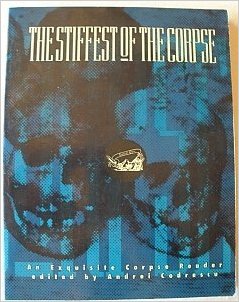

In midst of these strictly personal conundrums I did remember the obvious: Exquisite Corpse, for the entire three decades of its existence, made sure to recapitulate and memorialize itself, not just from issue to issue, but in three remarkable anthologies: The Stiffest of the Corpse: an Exquisite Corpse Reader, 1983- 1988 (City Lights, 1989, editor Andrei Codrescu), and Thus Spake the Corpse, an Exquisite Corpse Reader 1988-1998, Volume I, Poetry & Essays (Black Sparrow, 1999) and Thus Spake the Corpse, an Exquisite Corpse Reader, 1988-1998, Fictions, Travels & Translations (Black Sparrow, 2000), editors Andrei Codrescu and Laura Rosenthal. We closed the twentieth century by collecting ourselves, but kept going into the twenty-first full-speed-ahead on the internet, one of the first publications to do so. We almost invented Facebook, when we opened a “chat room” to accommodate real-time conversations on the material in the cyber-Corpse (as we briefly called it). The chat room turned into an unmanageable din of conversation about everything in the world, a process that we tried to manage by first hiring a “moderator,” then giving our most-often present voices their own section or “channel.” If we hadn’t been so hungup on “content,” so-o-o twentieth century a habit, we’d have let everyone make their own affinity circle in their own room where they could post whatever they wanted to. The curse of being in the avant-garde, even by five seconds, is not getting the money, plus missing the very future you inhabited for those five seconds. Vindicated prophets end both poor AND condescended to by the mobs for whom they opened the doors. Serves them right. “There is no such thing as an avantgarde body,” to quote the poet.

Given these insurmountable alps of memory, prose, and denial, I thought that it would be best to reproduce the cover and the editorial of Exquisite Corpse: a Monthly of Books & Ideas No. 1 (January 1983), offer the simple and touching story of our first stab at financing, the hallucinatory moment when we captured our first backer, and provide some insight into what made our magazine so extraordinary. This story is written now, as if never told before (and in truth, never in such luxuriating detail). I hope it “works,” as we used to say in that high age of poesy when Labor was admired and literature was composed of “works” we produced through high-minded Labor.

The Birth of Funding, or The War of Zeroes

The financing of the first issue was borne by the University of Baltimore, thanks to the English Department Chair, Lawrence Markert, who earned himself a title on the mast for his good work. (And publication of two of his poems which, having been rejected by the academic quarterlies, belonged by default to the Rebels.) Continuing to publish was another matter, but fate intervened. (As did “faith,” later).

I had been writing Op-Ed essays for the Baltimore Sun to earn extra cash; a reader wrote to me at the paper, asking for the honor of my acquaintance at a special dinner to be held before his impending demise from cancer. Even if I hadn’t been the editor of the Corpse, I’d have responded positively, but dinner with an imminent corpse looked promising, especially since the soon-to-be deceased was the wealthy owner of six bowling alleys in the Baltimore area.

I taxied up on time in what looked to me like a ritzy suburb, with a stack of Corpses No. 1 under my arm. The host was a roundish pale man planted in a deep armchair, being tended by a chain-smoking young-middle-aged woman with red toenails in open-toed sandals. A morose young man dressed in a business suit was planted in another deep chair opposite the host, tended in his turn by his anxious young wife, who turned out to be the host’s daughter. I took a seat and a double-Scotch, after placing the Corpses ostentatiously on a tiled table holding a flower vase with plastic tulips. An ashtray joined the stack of Corpses and the tulips, and I lit up. My smoking visibly cheered up the hostess, and visibly depressed the young couple. The host looked sedated and unreadable. We exchanged pleasantries, as I looked for an opportune moment to make my case for a Corpse subsidy to the dying bowling alley king. I couldn’t quite find it. So I drank. And smoked. The red-toes hostess started to have quite a good time, and I was soon racing her chain-smoking with my own, as the other couple sank into deeper gloom. I couldn’t smell anything coming from either the dining room or the kitchen, so I started to doubt that dinner would ever come. I drank more. And then we ran out of cigarettes.

The smoker jumped to her feet and announced that she was going out for cigarettes, did I care to join her? Yes, I did, and we were soon racing in her new Mercedes convertible to a convenience store in the ghetto that started just outside the ritzy burb. On the way I found out that the driver was the bowling alleys mogul’s mistress, and that she had been chosen to entertain the B-list of people the mogul wanted to meet before he died. The wife, who lived in a much bigger house, tended to the A-list. This information cheered me up considerably, since I felt that the Corpse was very much in the same position versus the mainstream as the mistress was to the wife. Come to think of it, Literature, for which both the mainstream and Bohemia worked, was also on the verge of dying. I was definitely going to get some money out of the old Bowling Macher. When we returned, in an even better frame of mind, with a carton of Marlboro Lights and another bottle of Scotch (opened and heartily tested), I smelled Dinner.

Dinner was in a solid middle-class dining room set with a flowered table-cloth, linen napkins and wine glasses. The host was lifted and deposited at the head of the table by his mistress and son-on-law. The louvered door of the kitchen swung violently open. A Caribbean servant with a yellow chignon on her hair came though with platter of ceviche that she spooned with undisguised hostility on everyone’s appetizer plate. She soon (too soon!) followed this with a soup tureen she splashed into soup bowls, and disappeared without a word. I looked at our dying host for a clue about what had just happened, or maybe a word or two about the menu, but he had started on his soup with eyes on the spoon.

This was the time to get going, so I said that the magazines I had brought with me were for everyone in the room, I hoped they enjoyed the fresh literature of them, and that, one day, the Exquisite Corpse would be renowned, if the God or Moolah favored us. I kind of garbled the word “corpse,” embarrassed by the obvious, but the old man’s interest was piqued. He looked out of the spoon. A desultory little conversation flared up, concerning the literary taste present, consisting as I recall, of solid best-sellers and articles in The Baltimore Sun. The son-in-law also mentioned the Bible, and the mogul’s spawn nodded. I said, Great Book! The mistress made a sound between Phooey and Yick. The dying was silent.

A cold and indifferent slab of poached salmon followed, hurled on plates by the cook, with a hostile force that had increased since the ceviche. I wondered if it was poisoned. During the removal of the mostly untouched fish, and before the arrival of the rhubarb pie, the old man motioned his helpers to take him to an armoire in the corner of the room. From there he extracted a check book and a fountain pen, and was taken back to the table. He asked me how much my little publication needed for printing another issue, and I said without hesitating, “Thirty thousand dollars.”

The son-in-law gasped, but the old man had already started writing the check. I spelled both “exquisite” and “corpse” for him. I mentally urged him on as his hand began forming zeroes: each movement of the pen revved up my silent urging. He had made at least two zeroes when his hand stopped and the hand hovered in the air. I felt the eyes of the son-in-law locked on the old man’s wrist, holding it with invisible fury. The hand, caught between my pushing it to move and the son-in-law’s paralyzing stare, stayed in the air.

“As your accountant,” said the son-on-law, without losing his grip on the hand, “I would advise you to think before making a big donation.”

I redoubled my psychic force: if Uri Geller could bend spoons, I could surely make a feeble old hand make another zero. Both son-in-law and I looked at each other at the same time. It was War. The War of the Zeroes. Simultaneously we returned to the wrist. It had ceased moving. The mogul passed the check to the mistress who took a quick look and handed it to me. It was for $3,000 dollars. I had lost. I’d been this close (makes teensy two-fingered gesture) to causing the writing of another zero.

No matter. It was enough for another issue of the Corpse.

The only shadow over this auspicious beginning was that we made our patron a “lifetime subscriber,” and he died shortly before the second issue. We faithfully sent every issue to his mistress’ house, until one was returned two years later with the “no known addressee” stamp. The ritzy suburb had become a slum by then.

Corpse Readers, Take Heart

I moved Exquisite Corpse: A Journal of Books & Ideas to Louisiana in 1984 when I went to teach at LSU in Baton Rouge. Since its founding in January 1983 in Baltimore, the Corpse, as the aficionados intimately call it, delighted not-so-innocent readers and catered to the craven complexes of overeducated esthetes, while also pleasing the autodidact lumpenproletariat on those long American afternoons by the Kerouakian railroad tracks now known as Starbucks. In other words, we fed the souls of both the jaded and of those too young to drink. We also enraged the literary establishment, garnering resentment, jealousy, damnation, and three threats of never-materialized lawsuits. From the very first issue, the Corpse attracted an energetic and sophisticated cadre of writers united by a kind of suicidal fearlessness specific to eighties America. In 1983, American literature had settled into a cozy bubble of MFA-program McWriters buttered with post-graduate NEA fellowships. American poetry was increasingly going back to the esthetics of the 1950s under the tutelage of impressionist critics like Helen Vendler of Harvard. Alongside prosaic confessional drivel in “free verse,” throwback versification calling itself “the new formalism” captured the workshops and the university quarterlies. American fiction began returning to psychological realism and sentimental autobiography. The fury of the establishment at having its nap disturbed by experimental writers in the sixties and seventies (and by modernism, surrealism, and post modernism before that) resulted in the return to a literary landscape H. L. Mencken had once called “the Sahara of the Bozarts.”

Taking potshots at this new status quo would have been like shooting fish in a barrel, but for the fact that the new reaction was (and is) huge. This was just fine by the Corpse, which relishes a fight the way academics crave prizes. It turned out, however, that fighting was not what the Corpse turned out to be about. After the initial skirmishes with some of the more visible capos of the new retrenchment, it became evident that a community of terrific writers existed in pristine disdain of the mainstream, and their works made the Corpse an important literary magazine. These writer embraced a variety of esthetics and were part of different scenes: New York School and Black Mountain poets, West Coast surrealists and eco-surrealists, ethnic accentualists, Iowa actualists, midwestern abstractionists, southern minimalists, and San Diego maximalists. The editor’s eclectic pleasures were further enhanced by the absence of biographical notes. From the beginning, Exquisite Corpse was conceived as a newspaper, to be read for the news within, not for the glamorous bios of recent conquerors of the Amy Lowell Traveling Fellowship plus glam shot. We began on page one with debate and controversy and moved, like Don Quijote, from windmill to windmill. Each issue had its own story pieced together by its contributors exactly like a “cadavre exquis,” the collaborative form that the French surrealists had enjoyed in the 1920s, from which Exquisite Corpse got its name. The Corpse, like Don Quijote, or perhaps Pantagruel, was also dedicated to the blurting of genres, demolishing distinctions between poetry and prose, lyric and reportage, essay and manifesto. In addition to poetry and a sprinkling of fiction (there was an inexplicable editorial bias against fiction), essays, letters, and art, the Corpse published “bureau” reports from various parts of the world, and a great many translations.

The Corpse in Louisiana (1984–1998) had two distinct periods: the first (1984–1990) was more or less an extension of the Baltimore Corpse, tropicalized by the environs; the second (1990–1998) was the era of the Body Bag. In its first Louisiana stage, the Corpse drew its energy from early contributors to the magazine and material solicited by the editor, with less than twenty percent of its contributions coming over the transom. There was also a nameless and invigorating force emanating from the diffuse hostility of the academic environment which, in those days was (and weakly still is) a bastion of New Criticism reincarnated as Southern-boy hickism. In the second stage, with the addition of Laura Rosenthal’s column “Body Bag,” which answered would-be contributors directly in the pages of the magazine, there was a sudden influx of young, new, hip voices into the Corpse. We were discovered by another generation of literary revolutionists who found in the tone of the magazine a perfect medium for their pop-culture-informed skepticism, violence, and humor. During this time, more than ten thousand literate, amused, hungry readers took the Corpse. The audience widened from just writers to readers interested in culture and, to some extent, the Corpse became a general culture magazine. Corpse essays were reprinted in Harper’s, Utne Reader, Playboy, and other mass-circulation magazines, and Corpse poets started winning awards (!), such as Pushcart Prizes, and inclusion in anthologies like Best American Poetry. We didn’t feel that such successes created any painful dilemmas, preferring to believe instead that “grownup” culture had finally tired of academic pieties and found the Corpse tonic and necessary. The initial critical attitudes of the Corpse became an inspiration for dozens of small magazines, zines, and newsletters. The world was catching up. At this time, more than seventy percent of our material came over the transom from writers unknown to us, but who had caught perfectly the Corpse je-ne-sais-quoi. ? years ago we changed the name of the publication to Exquisite Corpse: A Journal of Letters & Life, because we felt that it more accurately reflected our turn toward topics of wider interest.

Academic hostility continued unabated, however, because the retros in charge of the pathetic literature pie resented having any part of their wobbly conformism questioned. The problem with the wimps, Jim Gustafson once said, is that there are so many of them. You said it, Jimbo. Every year they multiply to the point where they cover the sky like a locust plague, leaving room only for their own reproduction. No matter. We have our own sky. And it’s a cybersky. In 1998, tired of mountains of paper, but also fearful of inevitable institutionalization, ossification, poetry fatigue, and literary ennui, we. suspended publication of the paper Corpse, taking it into cyberspace. The Cybercorpse can be found at: http://www.corpse.org. The Cybercorpse is still the Corpse, but it is more fluid, subject to instant change and, above all, not so labor-and time-intensive for us. And the trees are ecstatic.

[1] Portions of this essay originally appeared in the introductions to [insert full citations later]

[2] In the U.S. we don’t jail writers for political opinions, though it might have a salutary effect on public discourse. At the very least, we should jail writers for being boring. In 1983 American literature, especially poetry, was a sluggish and tired beast (after its burst of energy from 1965 until 1977) feeding off the meager teats of government grants and badly paid college sinecures.